We believe that discussing project specifications at the onset of a project and getting clear and complete instructions is the first step in completing an e-Discovery project successfully. One of the questions we regularly ask is whether or not embedded objects should be extracted. Over the years, we have found that most of our new clients require an explanation of what embedded objects are and the pros and cons of extracting them.

We typically recommend extracting all compound documents. However, we feel it is important that what this really means is understood clearly and an informed decision is made based on case requirements. We have come up with a few points for you to consider when making such a decision that will hopefully help you determine which route you should take.

What are Embedded Objects?

Many file types, including Microsoft Office and Adobe Acrobat files, act as containers and allow other documents to be linked to them or embedded in them. For example, one can embed a file into an Ms Word document by simply dragging it into an open Word document.

Depending on the file type and method used, the embedded document may or may not be directly visible in its parent document. For example, the contents of a single-page Visio drawing inserted into an Excel spreadsheet can be visible when the spreadsheet is viewed, while a ZIP file or an MSG file inserted into a Word document would typically be displayed as an icon and its contents would not be directly visible.

Extracting embedded objects means that the e-Discovery software identifies each linked or embedded document and extracts it (and its children recursively) as separate records during processing. Additionally, a parent/child relationship is established between the container document and the files embedded in it.

Advantages of Extracting Embedded Objects

1. Completeness:

In some cases embedded documents would not be processed at all unless embedded objects are extracted. This could result in critical content being missing from your review database and production. Take a look at the following three examples:

Example 1: Documents Displayed As Icons

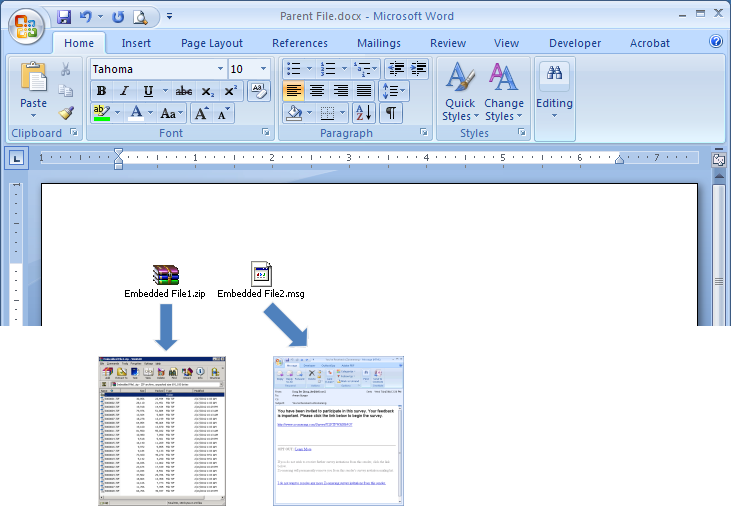

Contents of documents that are displayed as icons in their parent document would not be processed during e-Discovery unless embedded objects are extracted. For example, the embedded archive (Embedded File1.zip) and the embedded e-mail message (Embedded File2.msg) in Figure 1 below would not be extracted and processed unless embedded objects are extracted. Please note that the embedded archive contains several child documents, which also need to be extracted recursively.

Example 2: Charts in Ms Office Documents

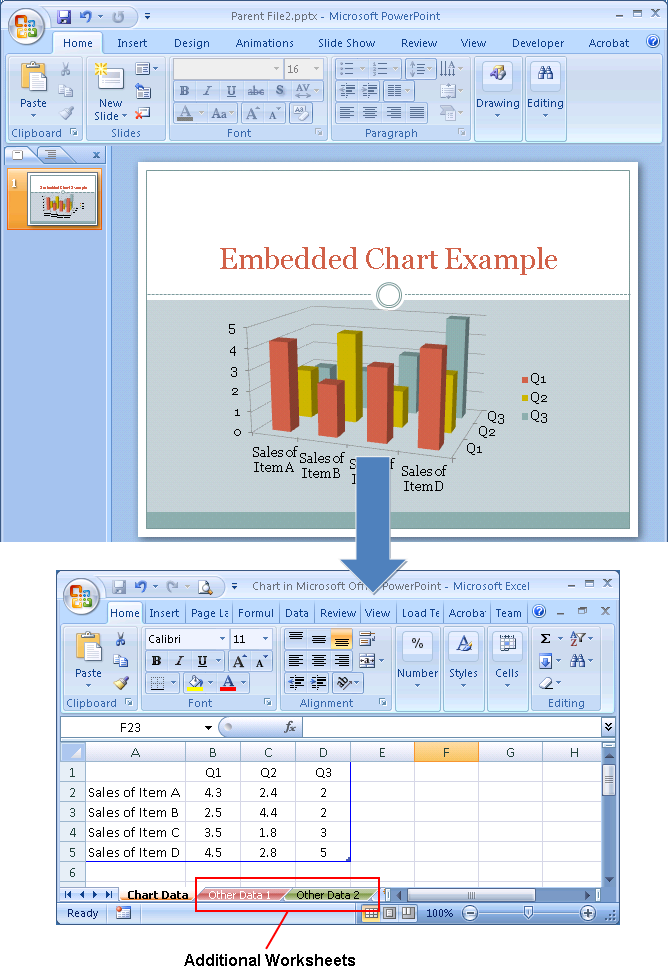

When a chart is created in or inserted into an Office document, the underlying data is typically stored as an Excel spreadsheet. While the parent document only displays the resultant chart, the underlying spreadsheet can contain much more data than what is represented in the chart.

The example Powerpoint presentation in Figure 2 contains an embedded chart. When the underlying Excel workbook is opened, it becomes apparent that the workbook contains additional worksheets.

Example 3: PDF Portfolios

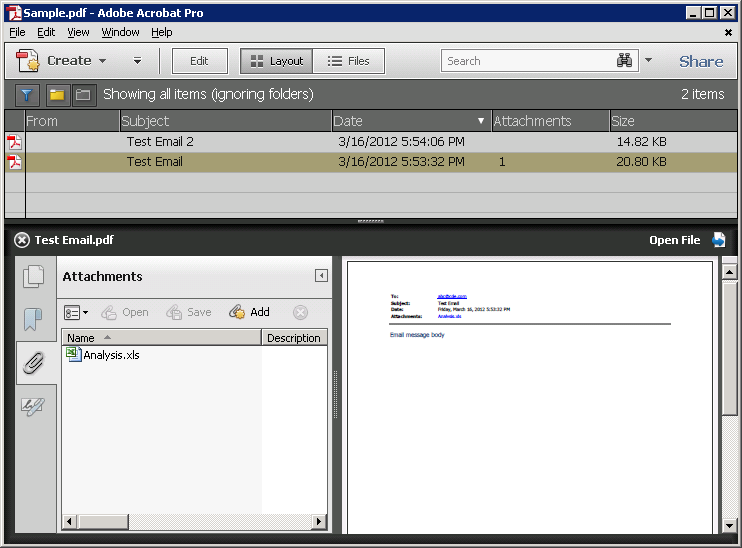

PDF portfolios contain multiple documents combined into a single PDF file. Documents contained in a PDF portfolio can be in various formats such as spreadsheets, e-mails, Powerpoint presentations etc. For example, one can select certain e-mail messages in Ms Outlook and convert them – including their attachments – to a PDF portfolio using the Adobe Acrobat PDFMaker Outlook Addin.

Figure 3 exemplifies a PDF portfolio created directly from Ms Outlook. One of the original e-mails contains an attachment (“Analysis.xls”), which was included in the portfolio as an embedded Excel spreadsheet.

Extracting embedded objects would ensure that each item in the PDF portfolio is extracted as a separate record and processed.

2. Fully Searchable Database:

Even though some documents may be visible in their parent document, they may not be fully searchable. Extracting embedded objects would ensure that each object is tested separately and OCR’ed if it is found to be missing extractable text.

Example 1: Images Embedded Into Searchable Documents

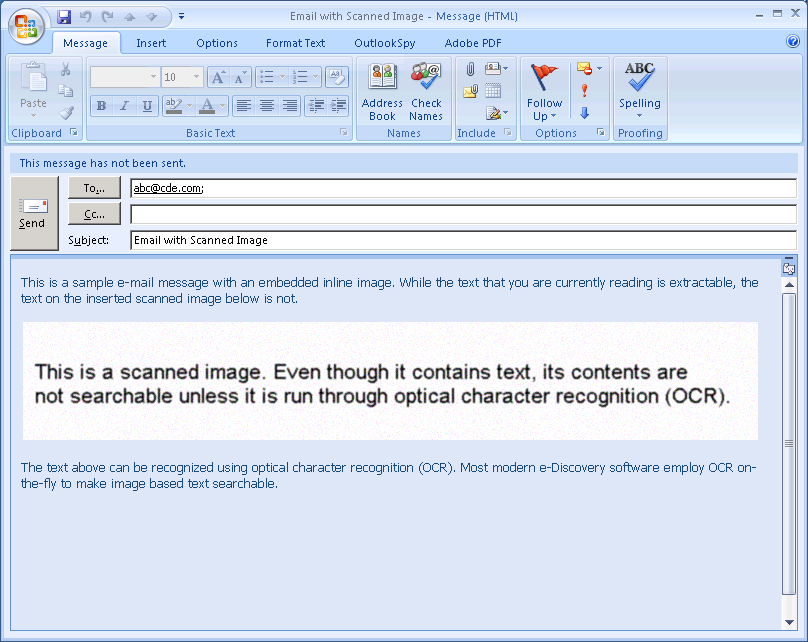

We often run into images embedded in otherwise searchable documents (for example, an excerpt from a scanned page embedded into the first page of an e-mail). This poses an interesting challenge. Most modern e-Discovery software detect non-searchable documents and run them through optical character recognition (OCR) on-the-fly to make them searchable. However, this analysis is usually performed at a document level, or page level. If a page contains some searchable content, it passes as searchable and is not run through OCR.

In the scenario below (see figure 4), we have a scanned image inserted into an otherwise searchable page. Most e-Discovery software would treat this page as a searchable page and would not attempt to OCR it. This would result in the text that could be extracted from the embedded image via OCR being lost. On the other end of the spectrum, if the scanned image is detected and the entire page is OCR’ed, the accuracy of text that could be extracted from the searchable part of the page would be reduced. Extracting embedded objects is a good option to make such documents searchable. When extracted, the embedded image would become a separate document itself. It would easily be detected as a document without extracted text and OCR’ed.

3. Native Productions:

Producing complex documents in native form is a common trend. One of the greatest risks of a native production is producing more than intended. For example, a spreadsheet or a complex file type can contain embedded documents that can be overlooked during review unless they were extracted as separate database records. Producing such a document in native format would mean giving your opponent data that you haven’t seen during review.

Extracting embedded objects helps make sure documents can be fully reviewed and minimizes the possibility of missing hidden content during review.

Disadvantages of Extracting Embedded Objects

1. More Documents to Review:

When embedded objects are extracted, separate database records are created for each child document. This results in a more crowded database, and potentially more documents to be reviewed. Imagine a Word document with 20 embedded objects: When embedded objects are extracted, the number of database records for this document increases from 1 to 21. If the child documents in turn have objects embedded in them, the number of database records after extraction can be even larger.

2. Duplicative Content:

Some embedded objects may be entirely visible in their parent document, making the extracted version redundant. Keep in mind that, even though the embedded object may be visible, it may not be searchable (see “Images embedded into searchable documents” above). So, this is not always a disadvantage.

3. Incomplete Objects:

Some embedded objects may not be complete, self-sufficient documents. Consequently, some of the extracted documents may not be directly viewable using their native application. Most modern e-Discovery software can work around this issue and still extract text & metadata from these objects and convert them to TIFF.

4. De-Duplication Issues:

Until recently, some off-the-shelf e-Discovery processing tools had problems when embedded objects were extracted and de-duplication was performed at the attachment family level. The issue was that some embedded objects were having minute differences in content (and therefore MD5 hash) each time they were extracted. Consequently, two identical compound documents were not being de-duplicated against each other due to the fact that one of their children had a different hash. To our knowledge, most software vendors have resolved this issue by now. That said, it is still worth keeping in mind when working with a new tool or service provider.

Conclusion

We are a proponent of extracting all compound documents. It is true that you may end up with more database records and it may take longer to review, tag and endorse the documents, but at least you can be confident that every document in the data set has been made searchable and reviewed. Bear in mind that it is easier to exclude database records from a production than it is to insert new records between existing documents. If you have embedded objects extracted up front, you would have the option to easily exclude them from your production if needed. On the other hand, if you don’t, and you later find out that some embedded objects should have been separate records, it would be more tedious to extract those objects after the fact and insert them where they belong.